After my first visit to the Toronto Krishna temple, my life was about to change in a major way. I had entered the medieval world of Krishna Consciousness, and like a moth into the fire, I had been consumed by this first experience. I immediately returned the next day. My friend, on the other hand, never returned. His curiosity had been satisfied and I never saw him again. His mission in my life had been fulfilled; he had delivered me to Krishna, but I could not get enough of the temple. I returned as often I could. The devotees urged me to drop every thing in my life and “move in.” In fact, I came very close to doing this, but somehow it never happened. I never “moved in.”

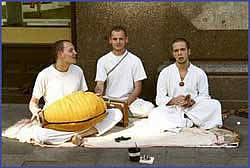

I would show up at the temple every Friday evening and Sunday afternoon without fail. I did this consistently for five years. Soon I even began to attend the 4:30 AM morning prayer program (mangala arati) a few days of the week! For the first year I never told my parents or any of my friends what I was doing. I would sneak downtown to the temple where I would chant, hear and read philosophy, take prasad and work in the temple. Mostly I would clean cooking pots or wash floors. Soon I would even change into a dhoti and put on tilaka (Hindu clothes and the clay religious markings).

In those days it was unusual for someone to be so involved and yet not move into the temple. It became standard procedure for the devotees to corner me in a room after the Sunday feast and lecture me about the evils of the material world. I was told that my parents were evil and that my school was a “slaughter house” for the soul, and how I should become a monk and leave the material world. The pressure was overwhelming. I suffered great psychological pain over this. I loved my parents and I wanted to continue my education into university. In those days most of the devotees were men in theirtwenties. A large percentage of them were ex-drug addicts and American draft dodgers avoiding the Vietnam war. I was never comfortable with these people. Had it not been for this one fact I indeed may have moved into the temple. I simply did not like the street element of many of the devotees. There was one devotee, however, that I did like. He was the temple president, Jagadish. Had it not been for Jagadish I could not have withstood the pressure that was put on me to move into the temple. Most certainly I would have left. Jagadish was college educated and could see that I needed to be handled in a different manner, so he created space for me in the temple society by telling the devotees to desist from pressuring me to become a full time member.

In those days the issue of religious cults was just beginning to surface in the public awareness. Soon the cult issue was to become a major topic in North American. A myriad of religious teachers both western and eastern would come to dominate the popular culture.

The Vietnam war played a major role in what happened in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. Anna, I am sure you have heard of the hippie movement with its free love, drugs, and rock and roll. The natural tendency to protest and challenge authority that is a part of normal adolescence was amplified a hundred fold by the Vietnam war. The youth of America rallied around this issue. In Canada there was no military draft and the country was not directly involved in the Vietnam war. Canadian youth were not coming home in body bags, but still we felt the questioning and the unrest that was churning in the land to the south. The pressure of the war put a huge number of rebelling youth onto the streets of North America. The atmosphere was ripe to collectively question the values of the society and challenge traditional ways. The rock music of this era reflected the turmoil of the times. Many youth explored religious mysticism, both Western and Eastern, in an attempt to find meaning in life. The Hare Krishna Movement was one such attempt. There were also many unorthodox Christian groups. I remember seeing “Jesus Freaks” and “Jew for Jesus” on the streets of Toronto. There was a general questioning of traditional values by the youth of the country.

I did not know this at the time, but the Hare Krishna Movement was really not a walk into something new. On the contrary, it was a venture into ultra-conservative values. It was religious fundamentalism, old time religion packaged in a new way. It is likely that my involvement in this movement was a retreat from the liberalism of the hippy movement to the security of traditional values. But not without a huge cost!

I did not know this at the time, but the Hare Krishna Movement was really not a walk into something new. On the contrary, it was a venture into ultra-conservative values. It was religious fundamentalism, old time religion packaged in a new way. It is likely that my involvement in this movement was a retreat from the liberalism of the hippy movement to the security of traditional values. But not without a huge cost!

Come take my hand, let’s take a walk,

Come take my hand, let’s take a walk,