“Art will remain the most astonishing activity of mankind born out of struggle

between wisdom and madness, between dream and reality in our mind.” *

February 12, 2009

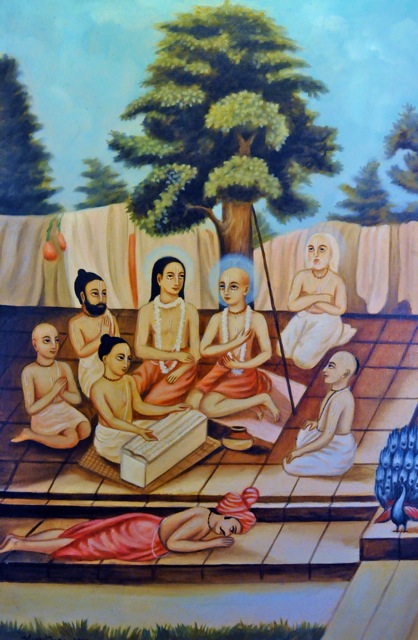

Some years ago I commissioned my first work of art. I had found a small black and white sketch of the 15th century Bengali saint, Chaitanya, that was apparently made during his lifetime. I found this while I was visiting Vrindavan, near Delhi. To this day I have never seen the original, nor do I even know where it is, but I brought this sketch back to Canada and had it painted by an ISKCON artist. You may not know, but ISKCON has an incredible tradition of art, particularly in oils. My artist, Vishnu Das, made a color painting of this black and white print, which I am proud to have hanging in my home even today. I consider it a rare and valuable work and since that time I have commissioned other paintings in a similar manner.

This was my first plunge into the world of art. At the time I “knew” the paintings were good because they were religious works. After all, the subject matter was spiritual and they were made by devotees. In those days my appreciation of art was primarily based on subject matter, realism, and who the artist was. In other words, if the subject matter was religious and the figures were realistic it was good art. My taste in art was mainly informed by my religious perspective. In truth I had no developed idea what constituted good art, and only now am I attempting formulate my opinions.

I know a family of serious art collectors. They have hundreds of paintings including Monets, Renoirs and even Picassos. Whenever I visit their home I take time to admire their collection and learn as much as I can. They are gracious and take pains to tell me the story behind each painting in their collection that interests me, who the painter was, what the subject matter is, some of the painting’s unique features, and so forth. They have taught me the value of art and encouraged me to look at art beyond my religious world. Partly through their encouragement, I have been inspired to travel to museums around

the world and see a few famous paintings. I am even interested to purchase some paintings of my own. I have talked to my friends about buying art, and apart from the logistics of purchasing it, buying through dealers or directly from the artist, their advise essentially comes down to “buy what you like.” This, of course, makes obvious sense, but what do I like? Should subject matter, realism and artist alone form the basis of my appreciation of art? Can my “tastes” in art even be trusted? As a child, I would make terrible combinations of flavor, a sandwich of peanut better and ketchup, and yet I thought it was a wonderful creation. Now, I would never consider such a combination of flavors. I have grown and my tastes have changed. So what constitutes good art? Is it beauty? Is art even supposed to be beautiful? What is beauty? Is there an objective basis for beauty or is it simply in the eye of the beholder?

As I read some of the literature on aesthetics I find that even this topic is filled with many of those unanswerable, impossible, “Is there a God?” questions that I no longer even try to answer. Attempting to address these kinds of questions in an absolute way was the endeavor of my youth. Instead, let me simply express my personal opinion on the subject matter of aesthetics.

I have resigned myself to the fact, I can never escape my religious view of life. As it is impossible to stop a dog from wagging its tail, my views on art and beauty must be consigned to my religious perspective. The Taittiriya Upanishad best captures my thoughts on aesthetics: “Beauty, verily, lies at the foundation of existence and having once experienced this, one becomes joyful.” (raso vai sah, rasam hyevayam labdhvanandi bhavati. 2.7.1) In crafting my translation, I need to explain the word “rasa.” Literally, “rasa” means water, juice, something that flows, and by extension, taste, charm and even beauty. Rasa is the taste in food as well as the enjoyment that comes through love and other personal relationships. Thus we can talk of the “taste” or pleasure that friends experience as a kind of rasa, or how a mother feels when she holds her child and sees its smile as a kind of rasa, or the enjoyment that two lovers feel towards each other another kind of rasa or “taste.” Rasa is aesthetic experience. So when the Upanishad says “raso vai sah” it is saying that aesthetic experience––enjoyment, taste and even beauty––lies at the foundation of existence.

This concept relates to another religious idea, which affects my world-view, namely, lila (divine play.) We hear of Rama lila and Krishna lila as the play of God in this world. Rama and Krishna are divine avataras, who descend into this earthly realm in order to “play” or enact pastimes of joy. Their activities in this world are called lilas. And they say this happens because God likes to play; that the desire for pleasure and enjoyment resides within Divinity as much as it resides within ourselves. In fact, we learn that the reason we have these tendencies is because God has them. We are “parts” of the whole and so we have the same qualities as the whole. But the concept is taken even further: not only do human beings have the desire to play and enjoy, all of life has this tendency as well. We, therefore, assert that life is nothing less than the search for pleasure and “play,” and, at the basic “animal” level, pleasure is sought in terms of food, sex, sleep, shelter, and so on. A plant moves towards the sun out of a desire to capture nourishment. This is pleasure. An animal eats and has sex. This is pleasure. In the beginning our desire for rasa manifests in terms of physical pleasures, but gradually with the increase of consciousness, along with learning and culture, this desire manifests in more subtle forms, in intellectual, emotional artistic and even spiritual ways. The world is full of sports heros and their spectators.

A reader of literature enjoys a drama. A scientist revels in solving a deep mystery. A connoisseur of art enjoys a painting. These are pleasure driven pursuits that are born from our very being. In fact, the Upanishad says, if pleasure did not exist, who would bother to breath and who would even want to live? The whole world is driven to maximize pleasure. There is even an orthodox Christian saying: Ultimately beauty will overcome the world. This is rasa and these are the ideas that lie at the foundation of my perspective, not only of art and beauty, but of life.

So what is the best art? For me, years ago, I was solely interested in Vaishnava art. I was pursuing devotional “tastes” (bhakti-rasa) but now, while my appreciation still moves in that direction, I have expanded my interests and I am now open to accepting other kinds of art, other kinds of rasas. My conclusion is simple: the best art is that which produces the greatest aesthetic response in the viewer. In other words, even if at some ultimate level, art and beauty are objective, that God’s standard of aesthetics is the test, beauty for all practical purposes is and always will be necessarily subjective. Every individual is his own judge of what is beautiful and what is pleasurable, and it is always according to consciousness, environment, training and other personal factors. I am, therefore, back to the opinion of my art collecting friends, “Buy what you like.” Only I would add, “And what you can afford,” for refined beauty comes at a price.

*Magdalena Abakanowicz